What you need to know about insulin resistance

Insulin resistance is a very common condition that often accompanies obesity or a diagnosis of pre-diabetes, type 2 diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), cardiovascular disease, and other metabolic conditions such as hypertension and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Have you been told you have insulin resistance? You’re not alone.

On the basis of NHANES 2011-2016 data, the prevalence of the insulin resistance syndrome (AKA metabolic syndrome) in the United States is 35%.1 Though the overall percentage has been fairly stable since the NHANES 2003-2006 data were released, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among young adults, Hispanic persons, and Asian persons has demonstrated a statistically significant increase.

When we look at people with obesity, the numbers get worse. Insulin resistance can be found in up to 44% of adolescents and 70% of women with obesity. Among adults with type 2 diabetes, the prevalence of insulin resistance rises to over 80%.2

Many people with the condition are unaware that they have it.

Also concerning? Insulin resistance is being linked to an increased risk of some cancers, Alzheimer’s disease, mental health disorders, and other chronic conditions.3

So how does insulin resistance start? How do you know if you are affected? And what can you do about it?

This in-depth guide will explain the science behind insulin resistance, help you understand why it happens and suggest the best way to get the condition diagnosed long before serious conditions like type 2 diabetes develop.

In a related guide, How to reverse insulin resistance, we will suggest concrete steps you can take to help your body become sensitive to insulin once more, and help prevent metabolic health problems — especially type 2 diabetes — from developing in the future.

What is insulin resistance?

Insulin resistance is when cells in your body do not respond effectively to the hormone insulin that is circulating in your body. This causes the pancreas to secrete even more of this important hormone in an effort to keep your blood sugar from rising too high.

Insulin has many roles. Its primary role is to keep our blood glucose levels in a very tight range — called blood glucose homeostasis. That’s because both too high and too low blood glucose levels are dangerous and damaging to the body. When glucose levels rise, more insulin is secreted. When glucose levels fall, less insulin is secreted. Since higher levels of insulin have been associated with numerous chronic health conditions, it makes sense that keeping insulin in a lower physiologic range may be better for your long-term health.4

Insulin also enables glucose to be used by cells for fuel or stored as glycogen in muscle and liver cells. Falling levels of insulin let the liver know when to make more glucose (gluconeogenesis) and rising insulin levels let the liver know when to stop.

Another crucial role is insulin’s regulation of fat storage. When insulin levels are high, it stimulates fat cells to take up glucose and turn it into fat (lipogenesis). Then, when insulin is low, it enables the body to take the fat out of storage and use it for energy.5

For someone who is metabolically healthy, this process works seamlessly to ensure a constant supply of fuel for the body. The problem arises when we are not metabolically healthy, which some researchers estimate may be the case for as many as 88% of Americans.6

The other important part of understanding insulin resistance is a condition that frequently coincides with it called hyperinsulinemia. When our bodies are exposed to an unrelenting supply of glucose, insulin is constantly secreted and remains chronically high — hyperinsulinemia.7

As we discuss in the next section, hyperinsulinemia is likely both a cause and an effect of insulin resistance.

Why does insulin resistance happen?

Genetic risk factors, environmental risk factors, and lifestyle factors have all been found to contribute to the development of insulin resistance.8

While some people may be genetically more likely to develop insulin resistance, the biggest impact has perhaps come from the change in our food environment in recent decades. Greater availability of cheap, energy-dense food and drinks may have led whole populations to adopt an unhealthy lifestyle, characterized by consumption of high levels of sugar and other refined carbohydrates. These simple carbohydrates are converted into large amounts of glucose that we may not need for energy, often resulting in much of it being stored in our cells or stored as fat.

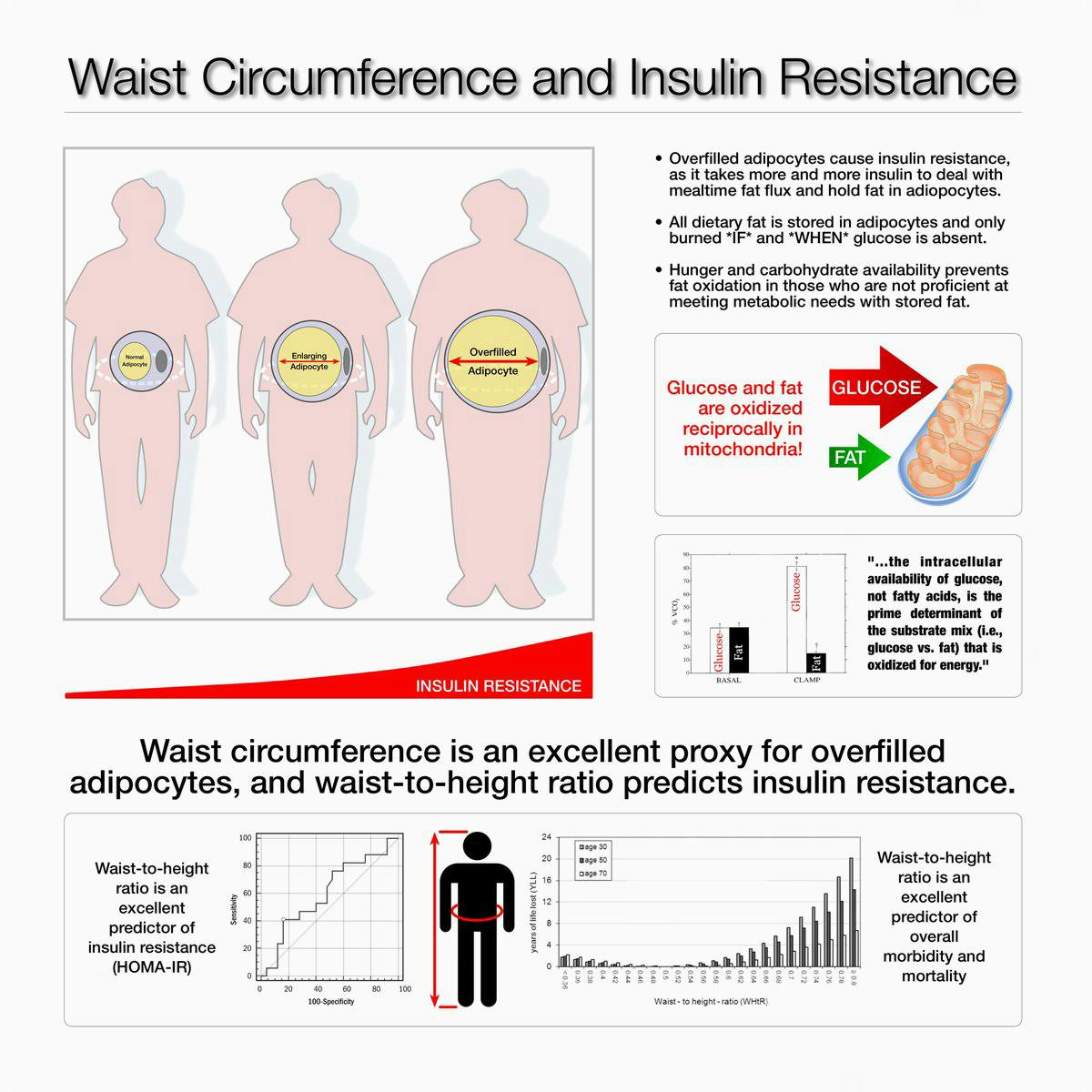

Scientists have elucidated many mechanisms and pathways that contribute to the development of insulin resistance. Interestingly, although we often think of insulin resistance in terms of the effect of insulin on glucose metabolism, one of the major causes is actually disordered fatty acid metabolism.

Scientific evidence suggests that fatty acids inappropriately accumulate in muscle and liver which then interferes with their cells’ ability to respond to insulin and take up glucose.9 One of the main questions, therefore, is how do excess fatty acids invade muscle and liver cells?

One mechanism involves the over-consumption of sugar, especially fructose, and particularly in the setting of excess caloric intake.10 Through multiple pathways that are beyond the scope of this article, this is thought to lead to excessive production of fat in the liver, which then leads to increased insulin resistance.

The same is likely true for a high carbohydrate, high fat diet in the setting of excess calories. Some studies suggest that specifically saturated fat – more so than MUFAs and PUFAs – is the offender that causes insulin resistance.11

Nonetheless, it is important to note that none of those studies included saturated fats in the context of a low-carb diet. Real world studies of low-carb diets with no restrictions on saturated fat have found improvements and even normalization of insulin resistance markers.12 This suggests that the problem may not be saturated fat itself, but rather the combination of saturated fats and a high amount of carbohydrates.

Additionally, as we review in our evidence-based guide on saturated fat, it is not accurate to refer to saturated fat as one thing. Saturated fat from cakes, cookies, and other baked goods could have significantly different effects on the body than more natural occurring saturated fats in meat and dairy.

Finally, a critical concept to understand is that elevated insulin itself may worsen insulin resistance.13 This creates a vicious cycle of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia likely made worse by ongoing caloric excess and weight gain.

Symptoms of insulin resistance

Insulin resistance has no obvious symptoms of ill health.

The main sign of the condition in many people — prior to being diagnosed with pre-diabetes or full-blown type 2 diabetes — is increasing abdominal fat, although not everyone will be aware of this.14

A prevailing theory of how insulin resistance worsens is that we each have a threshold level of fat that can be stored in our fat cells and when this is exceeded, our body starts storing fat in less ideal places — especially around the organs in our abdomen (such as the liver and the pancreas) and in our abdominal cavity. This is called visceral fat and when this fat starts increasing, it is a sure sign of insulin resistance.15

Other subtle signs of insulin resistance in some people are dark, dry patches of skin on the groin, armpits, or back of the neck, known as acanthosis nigricans.16 Skin tags — small fleshy growths — often on the neck or armpits can also be a sign of insulin resistance in some people, which is thought to occur because insulin is a stimulator of cell growth.17

Other than those symptoms, most people with early insulin resistance feel fine. It is only as blood glucose finally starts to rise that other symptoms of high blood sugar and type 2 diabetes may begin to show, such as frequent urination, excessive thirst, fatigue, and excessive hunger.

By the time someone is diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, they have probably had insulin resistance — or chronic hyperinsulinemia — for a number of years, perhaps even more than a decade.

Conditions associated with insulin resistance

The following health conditions are associated with insulin resistance:

- Obesity — Insulin resistance is associated with high insulin levels that may lead to increased body weight and obesity; obesity in turn leads to increased insulin resistance, thus creating a vicious cycle.18

- Pregnancy — Many women show signs of insulin resistance during pregnancy, especially in the third trimester.19 This is believed to be an evolutionary adaptation to provide sufficient glucose to the rapidly growing fetus. However, in some people, this can lead to gestational diabetes and high blood pressure.20 Proponents of the low-carb lifestyle believe this is a perfect example of how a normal adaptation designed to help ensure healthy pregnancy makes us more susceptible to metabolic disease in the context of a modern diet with foods high in refined carbohydrates, fats and sugars.

- Metabolic syndrome — This describes a collection of characteristics that are found in people with insulin resistance. There are a number of different definitions for metabolic syndrome that usually include an elevated fasting blood glucose level, high blood pressure, raised triglycerides and reduced HDL cholesterol, and increased waist circumference.21

- Pre-diabetes — Insulin resistance is associated with pre-diabetes. This is a situation in which blood glucose levels are higher than normal but not yet high enough for a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. The World Health Organization defines pre-diabetes as a fasting glucose of 110 – 125 mg/dL (6.1 – 6.9 mmol/L) or a 2-hour glucose of 140 – 200 mg/dL (7.8 – 11.1 mmol/L), as measured after a standardized 75-gram oral glucose challenge.

The US and some other countries use a different definition of FBG 100 – 125 mg/dL (5.7 – 6.9 mmol/L) or HbA1c 5.7 – 6.4% (39 – 46 mmol/mol). Since a diagnosis of pre-diabetes depends on an elevated blood glucose level, it implies that insulin levels have been chronically elevated for some time before the diagnosis. - Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) — Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common metabolic disorder affecting up to 10% of women of childbearing age. It’s a leading cause of infertility, and increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in later life.22 Women with PCOS tend to have elevated levels of male hormones, irregular or absent menstrual periods, and cysts on their ovaries, as well as insulin resistance. Other common symptoms are obesity, acne, male-pattern hair loss, and excess facial and body hair.23

- Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease — Called NAFLD, this is where there is too much fat stored in the liver. It may be the result of chronically high insulin levels and it may contribute to insulin resistance. While it is more common in individuals with obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes, it has been found to be associated with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia in lean individuals with normal glucose tolerance.24 Some people with NAFLD go on to develop liver problems, such as inflammation, scarring, and cirrhosis as well as liver failure.25

- Cancer — Insulin resistance is associated with an increase in risk of colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, pancreatic cancer, and breast cancer.26 It is not clear whether it is the insulin resistance itself or its relationship to other risk factors, such as obesity and high blood glucose, that contributes to the increased cancer risk. However, it is thought that chronically high levels of insulin may promote cancer growth and that reducing insulin levels may slow cancer growth, although more data are needed in this area to draw firm conclusions.27

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD) — Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are associated with increased risks for cardiovascular disease, in part because they are so closely associated with other CVD risk factors such as obesity and hypertension.28 Some studies suggest, however, that insulin resistance is an independent risk factor for heart disease.29 There are a number of theories about why hyperinsulinemia could trigger progressive heart disease. Most of them center around increased chronic inflammation and oxidation as well as direct vascular damage.30

- Alzheimer’s disease — Recent evidence suggests that Alzheimer’s disease could also be linked to insulin resistance.31 Studies show that those with diabetes are 60% more likely to develop dementia.32 Another study shows an increased prevalence of brain degeneration in those with diabetes.33 Although the exact mechanism is not proven, the theory is brain cells become insulin resistant and then cannot use glucose efficiently for fuel, thus leaving the cells starving for energy. The result is eventual progression to Alzheimer’s disease.

- Adaptive insulin resistance — Eating very-low-carb diets has been associated with the development of insulin resistance.34 However, some hypothesize that this is an adaptive physiologic response, and thus the name adaptive or physiologic insulin resistance.35

While this isn’t proven, we can hypothesize that if we stop eating sugar or carbohydrates, the amount of glucose in our blood will fall, at least to some extent.36 Our body will make sure, however, that our brain gets the glucose it needs by not sending as much glucose to the liver, fat cells or muscle cells (thus those tissues and cells appear “insulin resistant”). The brain can then use a combination of glucose and ketones as fuel.37The muscle and liver cells instead use ketones almost exclusively for fuel. Since this type of insulin resistance occurs with low rather than high levels of circulating insulin, it is not felt to represent the same dangerous condition as regular insulin resistance and may actually be a good thing.38

And one study in healthy volunteers clearly demonstrated improved liver insulin sensitivity with 36 hours of fasting compared to 12 hours, resulting in lower overall glucose and insulin levels, all despite what would be considered “peripheral insulin resistance.” The authors concluded that the liver insulin sensitivity is what makes this a healthy response, as opposed to hepatic insulin resistance in the pathologic version of insulin resistance.39

Diagnosing insulin resistance

How do you know if you have insulin resistance? What tests can you have that will confirm the diagnosis?

Unfortunately, insulin resistance is rarely diagnosed in most medical practices. It’s not because it isn’t widely prevalent in society, but because doctors don’t generally order the tests for it.40

Instead, doctors more often order the standard tests for diabetes that measure glucose levels: fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1c. However, by the time these are raised, insulin levels have likely been high for years, if not decades.

What can you test if you don’t want to wait until pre-diabetes or type 2 diabetes develops?

That’s simple: measure your waist and your height!

Waist-to-height: a powerful predictive measure

One of the earliest symptoms of insulin resistance is an expanding waistline as the body stores fat in your abdomen.

Even people with “healthy” body mass index numbers between 20 and 25 can have fat collect in their abdomens if they are becoming insulin resistant. This situation is colloquially called TOFI — thin on the outside, fat on the inside. The fat is literally wrapping itself around the liver, heart, kidneys, pancreas and other organs.

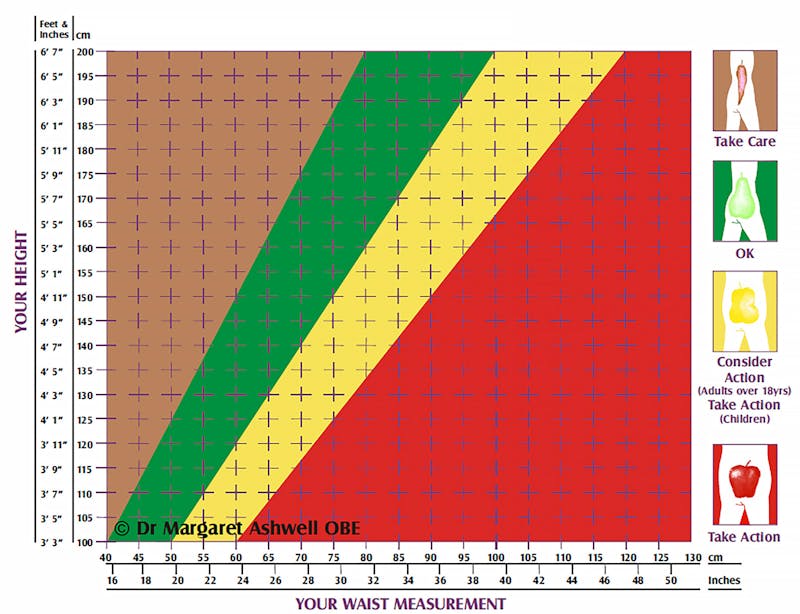

That’s why the size of your waist in relation to your height will tell you a great deal about your insulin sensitivity. Greater abdominal circumference in relation to height is related to an increased risk of diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and overall mortality even in people of normal weight.41 While this isn’t a perfect test, it is very easy to do, does not require your doctor to order it, and it can give you a good starting point to see if you have insulin resistance.

You don’t even need a tape measure. Just take a piece of string! The length of string around your waist should be at most half your height. If your waist is larger than half your height, you likely have insulin resistance.

One of the great strengths of this measurement is that your ethnicity doesn’t matter, nor does it matter whether you are male or female, young or old, short or tall, muscular or wiry — a number higher than 0.5 indicates an increased risk.42

Many health campaigns are now encouraging this simple idea: “keep your waist to less than half your height.”

Chart your waist and height

UK researcher Dr. Margaret Ashwell has pioneered the use of the Ashwell Shape Chart, which shows colored zones for waist-to-height measurements.

This simple graph can show you the danger zones. Just chart your waist measurement against your height and you can see where you fall on the graph.

Working with your doctor

As noted previously, most doctors don’t routinely test for insulin resistance. This may be appropriate when testing won’t change the recommendations for lifestyle modifications and/or treatment. However, testing can be very helpful when the results would clearly inform one’s choice of dietary modification or medical therapy.

If your waist-to-height ratio is larger than 0.50, you may want to talk with your doctor about ordering follow up tests to confirm that insulin resistance is present, and that you are at risk for blood sugar and metabolic problems.

You will likely have to ask for these tests. Don’t be afraid to be proactive and educate your doctor about these tests if you request them, as they may be worth the effort. However, be aware that not all health systems provide coverage for insulin levels and you may have to pay the full cost yourself.

We recommend three tests, all of which can be done fasting: insulin, triglycerides, and glucose.

- Fasting insulin and fasting triglycerides. Blood is taken first thing in the morning before you have eaten. Your insulin levels and your triglyceride levels are then measured. Triglycerides are a routine test that is easy to do, but fasting insulin, on the other hand, is less commonly ordered and you will likely have to ask for it. One study showed these tests had the strongest association with insulin resistance.43 Since fasting insulin by itself is only really helpful if very high (>20mIU/L) or very low (<3mIU/L), combining a mildly elevated insulin with elevated triglycerides (>150mg/dL) enhances the detection of insulin resistance.

- HOMA-IR- Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance. This is not a test in itself, but is a fancy name for a calculation using both your fasting blood glucose and fasting insulin levels.44 It takes those two variables and plugs them into a special calculator, giving you a numeric result. The concept is simple: how high does your insulin need to be to maintain your fasting glucose level? As an example, a fasting glucose of 95 mg/dL (5.3 mmol/L) with an insulin of 3 yields a HOMA-IR score of 0.7, suggesting good insulin sensitivity. But that same fasting glucose with an insulin level of 27 gets a HOMA-IR score of 6.3, suggesting clear insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. Any HOMA-IR score under 1 suggests good insulin sensitivity, while over 1.9 indicates early insulin resistance, and anything over 2.9 indicates significant insulin resistance.45

Summary

Awareness of and testing for insulin resistance, even with a simple waist-to-height measurement, should be more common among doctors and patients. If we wait for a rise in blood glucose, then we may be missing years of high insulin levels that could have been addressed.

Instead, we want to identify insulin resistance early so we can reverse it and prevent the dangerous consequences of metabolic disease.

If you have confirmed insulin resistance, a number of proven lifestyle changes may be effective to help reverse the condition, including a low-carb or ketogenic diet, exercise, better sleep, stress reduction, and tobacco cessation. Check out our in-depth insulin resistance treatment guide for more detailed information.

Did you enjoy this guide?

We hope so. We want to take this opportunity to mention that Diet Doctor takes no money from ads, industry or product sales. Our revenues come solely from members who want to support our purpose of empowering people everywhere to dramatically improve their health.

Will you consider joining us as a member as we pursue our mission to make low carb simple?

JAMA 2020: Trends in the Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in the United States, 2011-2016 [observational study, weak evidence] ↩

Pediatric Clinics of North America 2019: Childhood Obesity and the Metabolic Syndrome[overview article; ungraded]

Journal of Diabetes Research 2015: Population-based studies on the epidemiology of insulin resistance in children [observational study; weak evidence]

Diabetes Care 2006: Prevalence and determinants of insulin resistance among U.S. adolescents: A population-based study [observational study, weak evidence]

Minerva Endocrinology 2012: Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in overweight and obese women according to the different diagnostic criteria [observational study; weak evidence]

Diabetes 1998: Diabetes. 1998 Prevalence of insulin resistance in metabolic disorders: the Bruneck Study [prospective cohort study; weak evidence] ↩

International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020: Sarcopenic Obesity, Insulin Resistance, and Their Implications in Cardiovascular and Metabolic Consequences[overview article; ungraded]

Current Diabetes Reports 2017: Cardiometabolic Risk in PCOS: More than a Reproductive Disorder[overview article; ungraded]

Nutrients 2017: Isocaloric Dietary Changes and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in High Cardiometabolic Risk Individuals[overview article; ungraded]

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2001: Insulin resistance as a predictor of age-related diseases [prospective cohort study with HR > 2; weak evidence] ↩

Just because an elevated level of something is associated with disease, that does not prove that lowering it equates with better health. This is an assumption that needs to be proven in scientific studies. In the absence of those studies, we postulate that it would make sense, especially when accomplished via otherwise healthy lifestyle modifications. [expert opinion, based on hypothesis and synthesis of observational data; very weak evidence]

↩Clinical Biochemist Reviews 2005: Insulin and insulin resistance [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders 2019: Prevalence of optimal metabolic health in American adults: national health and nutrition examination survey 2009–2016 [observational study; very weak evidence] ↩

Diabetes 2012: Banting lecture 2011 hyperinsulinemia: cause or consequence? [overview article; ungraded]

Journal of Endocrinology 2017: A causal role for hyperinsulinemia in obesity [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Clinical Biochemist Reviews 2005: Insulin and insulin resistance [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Best Practice and Research Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2006: Pathophysiology of insulin resistance [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Journal of Clinical Investigation 2009: Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans

[randomized trial; moderate evidence]Molecular Medicine 2009: Short-term overeating induces insulin resistance in fat cells in lean human subjects [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

Diabetes 2010: Short-term overfeeding may induce peripheral insulin resistance without altering subcutaneous adipose tissue macrophages in humans [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

↩PLOS Medicine 2016: Effects of saturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, monounsaturated fat, and carbohydrate on glucose-insulin homeostasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled feeding trials [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩

Current Opinions in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity 2020: Effect of low-carbohydrate diets on cardiometabolic risk, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome[overview article; ungraded]

JCI Insight 2019: Dietary Carbohydrate Restriction Improves Metabolic Syndrome Independent of Weight Loss [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Obesity 2015: Weight loss on low-fat vs. low-carb diets by insulin resistance status among overweight adults & adults with obesity: A randomized pilot trial [moderate evidence]

In addition, the following study showed the low-carb, higher saturated fat diet resulted in lower serum saturated fatty acids and lower markers of lipogenesis:

Lipids 2009: Carbohydrate restriction has a more favorable impact on the metabolic syndrome than a low fat diet [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

↩Diabetes Care 2008: Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia [overview article; ungraded] ↩

One reason people may not be aware of this is the condition often called TOFI by the lay press, i.e. thin on the outside, fat on the inside. This means fat is stored inside the abdomen, where it may not be very visible from the outside.

↩Biochimica et Biophysica 2010: Adipose tissue expandability, lipotoxicity and the metabolic syndrome — an allostatic perspective [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 2004: Acanthosis nigricans associated with insulin resistance: pathophysiology and management [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Dermatologic Therapies (Heidelberg) 2017: Skin manifestations of insulin tesistance: from a biochemical stance to a clinical diagnosis and management [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Journal of Clinical Investigations 2000: Obesity and insulin resistance [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000: Carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in pregnancy: normal compared with gestational diabetes mellitus [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2003: Insulin resistance and its potential role in pregnancy-induced hypertension [overview article; ungraded] ↩

One definition of metabolic syndrome is meeting three or more of the following criteria:

- Fasting blood glucose above 100mg/dL (5.5 mmol/L)

- Elevated triglycerides above 150mg/dL

- High density lipoproteins (HDL) below 40mg/dL in men and 50 in women

- Elevated blood pressure above 130/85

- Increased abdominal obesity with a waist circumference over 40 inches in men and 35 inches in women.

Clinical Epidemiology 2014: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of polycystic ovary syndrome [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Journal of Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders 2018: Lean polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): an evidence-based practical approach [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Journal of Medicine 1999: Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance [case-control study; very weak evidence] ↩

Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials 2014: Non alcoholic fatty liver: epidemiology and natural history [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Current Pharmaceutical Design 2017:

PTEN, Insulin Resistance and Cancer[overview article; ungraded]Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 2010: The proliferating role of insulin and insulin-like growth factors in cancer [overview article; ungraded]

Oncogenesis 2017: Hyperglycemia exacerbates colon cancer malignancy through hexosamine biosynthetic pathway [mechanistic article; ungraded]

Endocrine Related Cancers 2015: Highly specific role of the insulin receptor in breast cancer progression [mouse study; very weak evidence] ↩

Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome 2019:

How the association between obesity and inflammation may lead to insulin resistance and cancer[overview article; ungraded]Endocrinology 2011: Minireview: IGF, insulin, and cancer [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Endocrine Reviews 2019: Insulin Resistance and Atherosclerosis: Implications for Insulin-Sensitizing Agents[overview article; ungraded]

New England Journal of Medicine 1987: Insulin resistance in essential hypertension [mechanistic study; ungraded evidence]

British Medical Journal Open Heart 2017: Added sugars drive coronary heart disease via insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia: a new paradigm [editorial; ungraded] ↩

New England Journal of Medicine 1996: Hyperinsulinemia as an independent risk factor for ischemic heart disease [prospective-cohort study; very weak evidence] ↩

Cardiovascular Diabetology 2018: Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease [overview article; ungraded]

Circulation 2002: Insulin causes endothelial dysfunction in humans [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic disorders 2013: Role of insulin resistance in endothelial dysfunction [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Lancet Neurology 2020: Brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders: mechanisms and therapeutic approaches[overview article; ungraded]

Journal of Diabetes, Science and Technology 2008: Alzheimer’s disease is type 3 diabetes – evidence reviewed [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Diabetes Care 2016: Type 2 diabetes as a risk factor for dementia in women compared with men: a pooled analysis of 2.3 million people comprising more than 100,000 cases of dementia [systematic review of observational trials; weak evidence] ↩

Neurology 2015: Type 2 diabetes mellitus and biomarkers of neurodegeneration [non-randomized study; weak evidence] ↩

Endocrinology 2010: Insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance are altered by maintenance on a ketogenic diet [rat study; very weak evidence] ↩

The following paper hypothesizes that insulin resistance played a role in evolution and may have been a natural adaptation to illness, injury or temporary starvation.

Metabolism 2013: Insulin resistance: An adaptive mechanism becomes maladaptive in the current environment — An evolutionary perspective [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Remember that the liver makes new glucose through the process called gluconeogenesis, and it also breaks down glycogen to release glucose into the bloodstream as needed. This is mainly why cutting carbohydrates from the diet does not lead to hypoglycemia. ↩

While the brain can use ketones for fuel, it cannot get all of its energy demands from ketones alone. See our guide Does the brain need carbs? for more information. ↩

This is an unproven hypothesis based on extrapolating data from other sources such as from starvation experiments and animal studies like the one cited here in elephant seals.

Frontiers in Endocrinology 2013: A non-traditional model of the metabolic syndrome: the adaptive significance of insulin resistance in fasting-adapted seals [animal study; very weak evidence]

Diabetes and Metabolism Reviews 1988: Mechanisms decreasing glucose oxidation in diabetes and starvation: Role of lipid fuels and hormones [mechanistic review article; ungraded]

↩American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology, and Metabolism 2021: Impact of prolonged fasting on insulin secretion, insulin action, and hepatic versus whole body insulin secretion disposition indices in healthy young males[randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Reasons for the lack of testing for insulin resistance include:

- Expense

- Lack of availability

- Lack of awareness of the utility of insulin levels.

- Awareness, but knowing that treatment may be the same regardless of insulin levels.

- Specific physical exam findings for insulin resistance obviate the need to test insulin.

- Insulin assays are not necessarily well-standardized across labs and there aren’t really clear diagnostic cutoffs. So, very low or very high levels are helpful, but in between levels may not be.

- Insulin assays are not necessarily reliable and reproducible.

- Long glucose tolerance tests are inconvenient to do.

BMJ Open 2016: Waist-to-height ratio as an indicator of ‘early health risk’: simpler and more predictive than using a ‘matrix’ based on BMI and waist circumference [retrospective observational study; very weak evidence] ↩

Obesity Reviews 2014: Waist-to-height ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: systematic review and meta-analysis [systematic review of observational studies; moderate evidence] ↩

Diabetes Care 2001: Diagnosing insulin resistance in the general population [non-randomized modeling study; very weak evidence] ↩

Diabetologia 1985: Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man [mechanistic study; ungraded]

Diabetes Care 2001: Homeostasis model assessment is a reliable indicator of insulin resistance during follow-up of patients with type 2 diabetes [nonrandomized study, weak evidence]

Medicine 2019: Optimal homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) cut-offs: A cross-sectional study in the Czech population [observational study, weak evidence]

↩As long as you have fasting glucose and insulin levels, you can access sites online to calculate the HOMA-IR for you such as this one. ↩